How working in the woods saved my life...

Why I left my teaching job to work at a Forest School on Hampstead Heath...

This is the first in a series documenting my transition from mainstream classroom teaching to outdoor, child-led learning. It’s a story of burnout, rediscovery, and ultimately finding a way to work that aligned with who I am.

I now work full-time as a remote tutor based in Cornwall. But before that, I was a Forest School teacher in London, working in the wild corners of Hampstead Heath—from the Kenwood Estate to Queen’s and Highgate Woods (essentially the same ancient woodland, divided only by a road). I came to Forest School after nearly two difficult years as a primary school teacher—an experience that left me drained and uncertain of my place in education. The transition to outdoor learning was unexpected, but it profoundly changed my life.

When I moved to London, I had just completed a Primary Education degree at Winchester University. I’d trained alongside three of my housemates and we shared an optimistic belief that we’d quickly thrive in the classroom and climb the ladder into leadership. I had recently got married, and my partner and I were moving into our first rented flat together—a tiny shoebox in North London.

During university, I had done pretty well in the assignments, and had lots of encouragement from my tutors, who to be honest were probably just pleased to be getting some men into teaching! I attended placements within Primary Schools, where in the 2nd and 3rd year, we effectively became the teacher in the classroom. It was during these placements that the first cracks started to show—signs that perhaps I wasn’t quite the natural fit for mainstream education I’d imagined. Even in a ‘teacher-lite’ role (where I didn’t carry full responsibility), I struggled with the relentless marking and admin, that often took over my evenings and weekends and even then I still wasn’t able to keep up. Towards the end of placements, although I did not understand it then, I would experience elements of burnout, rising levels of anxiety and panic, resulting in me taking sick days, generally just willing the experience to end. Considering this was going to be how I was expecting to spend the rest of my working life, I should have probably paid more attention to these early warning signs! Instead I chalked this down to getting used to the job and felt too embarrassed to honestly share how much I struggled with my housemates and tutors.

Starting my first proper position as a teacher in London, I put those experiences to the side and threw myself into the role. I was placed in Year 5 in a single-form entry school in northwest London. Before term began, already picturing myself as the hero teacher for these city kids, I was in early preparing my classroom and planning my first few weeks—bright-eyed and eager to impress. I was told that some children in the class had behavioural challenges and difficult home lives, but reassured that I’d have a strong teaching assistant and support as a newly qualified teacher.

As term began, I quickly realised I was in over my head. I didn’t have the skills—or the consistency in my behaviour management—to properly support the pupils who needed it most, and that soon started to impact the whole class. I still carry guilt about not being able to provide the firm boundaries those children deserved, and I saw how that lack of structure affected everyone’s learning. I ended each day exhausted, worn out by constant low-level disruption. Even by the middle of the first term, I found it hard to motivate myself to do even basic tasks like marking and planning.

I would stay at school until 6 or 7pm, after arriving at 7am, but spent much of that time trapped in a cycle of procrastination. I’d go home knowing the next day would be worse for lack of preparation, and that it would make managing the class harder again. Even writing this now brings up the memory of that constant, gnawing anxiety.

The anxiety and frustration began to manifest itself in different ways, mainly in constant worrying about the next day as I went to sleep, and how I would deal with the more challenging needs of some of the children. I would often dream about worst case scenarios, and even once woke my partner Es up shouting, convinced that the whole class was hiding underneath my bed, waiting for me to teach a lesson I hadn’t prepared! I remember walking down to the school from my house in the dark during that bitter autumn feeling completely defeated before the day had even begun, definitely not a mental place from which I could inspire my class to learn!

I made it through to Christmas, bolstered by colleagues telling me it was all part of the “baptism of fire.” I think I already knew this wasn’t sustainable, but felt too scared to admit that. I’d told everyone I had wanted to be a teacher since I was in secondary school and so admitting that it wasn’t working felt like a collapse of identity. That New Year’s Eve, I sat in my classroom marking books, my partner helping me. I felt the sudden urge to ring my headteacher and quit there and then. Es sat with me and told me to not make the decision out of fear, but to wait till I felt more grounded.

Some of the children who had needed the most support left later in the year, making things a little easier, but I still felt traumatised by the winter months. I’d had periods of severe anxiety and insomnia, and I genuinely dreaded going in. Over the long summer break, I finally had time to decompress—and for a few weeks, I even managed to forget I was a teacher. When September rolled around, I decided to give it another go. Maybe it had just been a rough first year, and my hard won experience would see me through, like some kind of war veteran.

But as soon as the new class started, the same issues emerged. I felt the familiar anxiety returning, stronger this time. My procrastination worsened and my self-esteem plummeted. I took more sick days. In moments of desperation, I considered anything— jobs in accountancy, retail, something, anything else. I thought about retraining as a counsellor even though I’d never had counselling in my life!

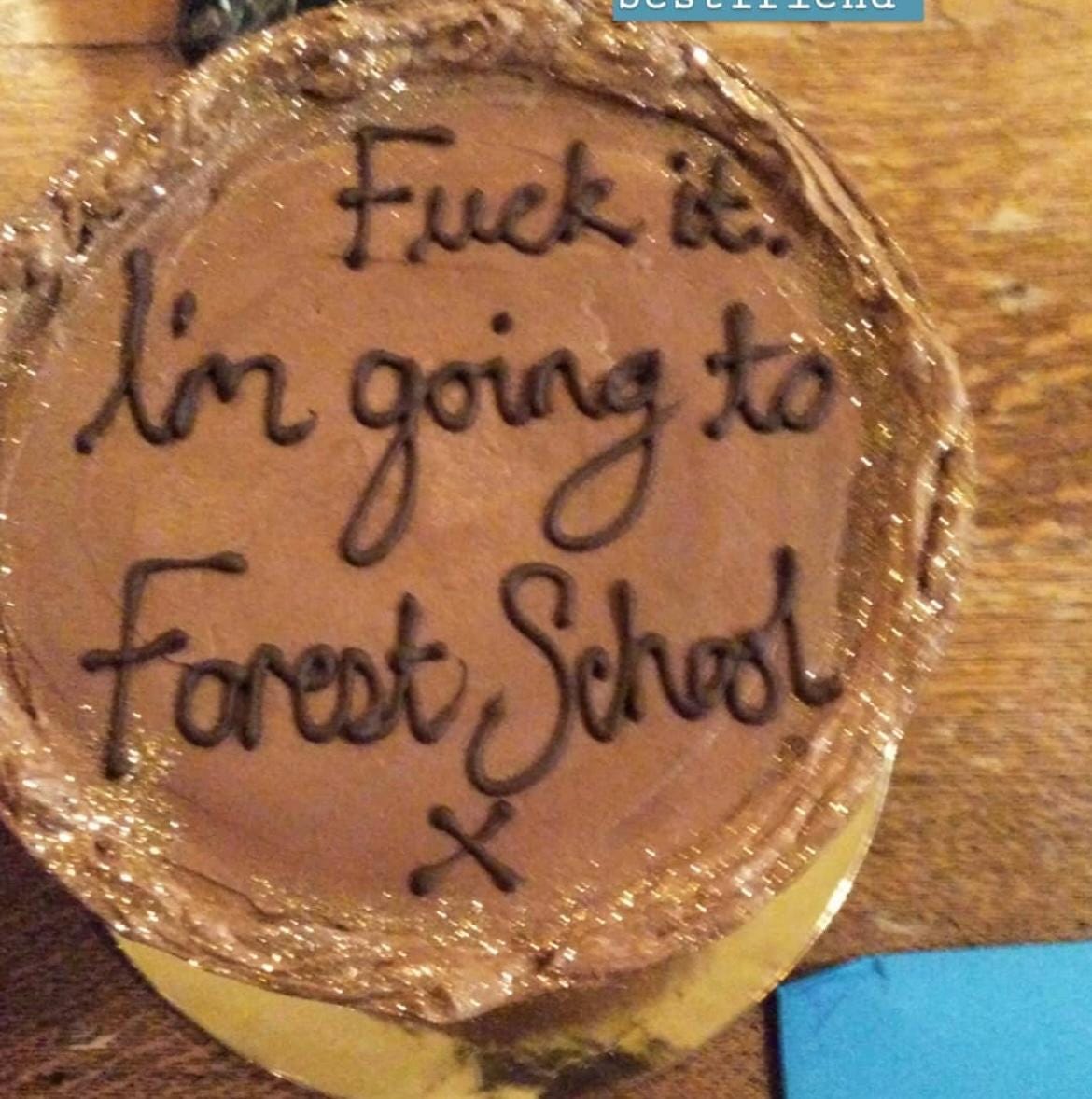

Es stayed calm and reminded me of what I was too deep in the struggle to see: I still cared about children, and about education, this just maybe wasn’t the right form of it. Back at university, I’d written a dissertation on the benefits of outdoor learning. Es connected the dots I couldn’t. One Saturday morning during the Christmas break, she sat me down and showed me a list of five nature schools and nurseries. She’d written out their names, commute times, and even phone numbers.

It made immediate sense. The idea of teaching outdoors sparked something in me. I called and emailed them all that weekend. The closest to home was Into the Woods, an outdoor nursery based in Hampstead Heath’s Kenwood Estate. I arranged a visit for February 2019—just as the "Beast from the East" snowstorm arrived in the UK. London doesn’t often get snow like that, but this time it blanketed the city. On the morning of my visit, I called the nursery, assuming they’d be closed. To my surprise, Julia, the nursery manager, responded brightly that they were most definitely open.

I left my flat and began a walk across the heath, which had transformed into a Narnia-esque wintry landscape—snow-blanketed trees, frosted bridges, and even a single lamppost, standing alone in the white. Looking back, I felt a little like Lucy, opening a door into a new world, full of nervous excitement.For a moment, I completely forgot my responsibilities as a teacher and entered that rare, child-like state of presentness that snow can still bring—even to the most stressed adult.

When I arrived at the converted estate dairy—shared by the nursery and the Kenwood estate team—I walked into cheerful chaos. Layers of waterproofs and thermals were scattered across the floor, and five staff members were hurriedly pulling on clothes, stuffing trolleys with first-aid kits, snacks, and books. They joked and chatted with each other casually, with little of the tense nervousness I was used to before a school day started.

Julia, who I’d only spoken to on the phone, introduced herself. She was wrapped in a huge scarf and a bright blue coat that looked like it belonged on a polar expedition. She led me outside to come and meet the first children, who were beginning to arrive. We stepped out onto the white lawn. I was completely underdressed in my chinos and car coat. The view stretched over two big leafless trees surrounded by thick snow. Then, a tiny figure bounded around the corner in a snowsuit, looking more like a mini Everest climber than a nursery child. In his mittened hand was a snowball, which he launched at Julia. She laughed and flung one back. A snowball skirmish broke out between teacher, child, and the child’s parents. I stood watching, grinning.

Something had shifted inside of me. If this was how the day began at Forest School, I knew I wanted in.

Hello, I'm so glad its helpful for you! So the forest school I worked was an outdoor nursery which I think translates as Kindergaten age, the children were all between 2 -4 years old.

Es to the rescue. Lovely piece.